History of Unitarian Universalism

Michael Servetus

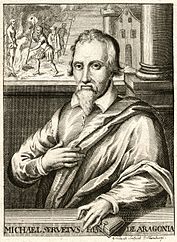

Michael Servetus

In 1553 Michael Servetus was burned at the stake by Calvin.

Servetus, or Miguel Servet, was a Spanish Catholic who had become a geographer and editor in Paris, then a physician in southern France. In that year, he published a book, The Restitution of Christianity, in which he repeated assertions he had made in his earlier writings: That the doctrines of the Trinity and infant baptism made no sense.

The order for his arrest went out, and one Sunday morning soon thereafter he was spotted in a Genevan church, arrested, tried for spreading heresy and executed, with a copy of the Restitution strapped to his thigh (or, according to some sources, his arm).

The death of Servetus was approved by the church leaders of the time, but not by all its ministers or laymen. His writings provided a stimulus for, among others, two Italians living in Zurich: Lelio Sozzini, who was impressed not only by Servetus’ doctrine but also by his method of thinking — basing his thought on reason as much as Scripture — and Giorgio Biandrata.

Both men went to Poland in 1558, Sozzini for a few months and Biandrata to stay. There they joined the liberal wing of the Polish Reformation, the so-called Minor Church, and helped to make it part of the Reformation’s left wing. When Biandrata left Poland five years later the Minor Church was in a weak condition, but twenty years after that its leadership was taken over by Fausto Sozzini, or Faustus Socinus, who had first absorbed liberalism from the papers willed to him by his uncle Lelio.

Socinus made Poland a stronghold of liberal Christianity for almost a century; the church he built and the theology he articulated were known as Socinianism, until the movement was destroyed by a decree banishing all Socinians. Some of the exiles went to Transylvania; others to Holland, the country where they felt they would have the best chance of practicing their religion.

Meanwhile Biandrata had been called to Transylvania to be the personal physician of King John Sigismund. There he spoke of his religious views with some of the leading citizens of the country, one of whom embraced them with alacrity. This was Ferenc Dávid, a former Catholic who had embraced Lutheranism and then Calvinism, and who under the influence of Biandrata now became the leader of the anti-Trinitarian movement.

In 1568 Ferenc Dávid succeeded in persuading the king to issue the broadest toleration edict in Europe at the time, granting the Socinians the same level of toleration as was already enjoyed by the Catholics, the Lutherans, and the Calvinists. (It was in the same year — 1568, just 15 years after the death of Servetus — that Dávid coined a new name for his group: Unitarians, or believers in one God, not three.)

But Sigismund’s sympathy for the Unitarians did not extend to his successor, and in 1578 Dávid was thrown into a dungeon, where he died a year later. The Transylvanian church survived, though greatly weakened, through the centuries. Its direct descendent today is an ethnic, Hungarian-speaking denomination in Rumania.

Holland, we may remember, was the refuge of some of the Polish Socinians; there were also many contacts between one of its religious groups, the Remonstrants, and Transylvania. These Remonstrants were in the late 17th century printing English translations of Socinus and other liberals, and smuggling them across the Channel. A result was a growing interest in liberal religion among certain English churchmen, among them the Anglican Theophilus Lindsay and the chemist Joseph Priestley, who professionally was not a scientist but a Dissenting minister.

Priestley was the leader of the group that in his time came to be called Unitarians, until he was driven from England in 1794 by continuing threats to his life. So he came over to the new United States of America, where he settled in Northumberland, Pennsylvania, meeting regularly with a group of twenty to thirty people to discuss religious matters. This was not a formal church; but two years later he helped found in Philadelphia the first American society calling itself Unitarian. Even so, Priestley did not originate liberal Christian thought in this country.

Half a century before Priestly there were two ministers, Charles Chauncy and Jonathan Mayhew, who had preached heretical doctrines including the unity of God; and in 1785 their disciple, James Freeman, persuaded the members of his church, King’s Chapel in Boston, to adopt changes in the wording of its Prayer Book which made it de facto the first Unitarian church in America, though it never acknowledged the fact in its name.

The later history of the Unitarian movement in North America is one of change and development, a change much more striking than what has taken place in any other national Unitarian movement. For whereas the Unitarians in Rumania worship and believe today just about as they did four centuries ago, and those in England do not seem at times to have changed much more, in this country most observers would say that we have little in common with the Philadelphia Unitarians to whom Joseph Priestley spoke in 1796.

In the 19th century our own great Trinity — Channing, Emerson, and Parker — moved us from a totally Christian body to one open to the other religions and philosophies of the world, and in the early 20th century Curtis Reese and John Dietrich allowed us to embrace even a non-theistic religion.

The same is true of the other half of our UU movement. In England in the 1760s James Relly preached a doctrine of universalism, which held that since God was a loving God, it was inconceivable that he could condemn anyone to everlasting torment, and there were therefore no such place as Heaven or Hell; all people would eventually be saved. A disciple, John Murray, came to North America in 1770 and began preaching the doctrine, which merged with views already being propounded, especially in Philadelphia by Benjamin Rush and Dr. George de Benneville — yet another physician prominent in our history.

Murray went on to found Universalist churches in New England, but in the following century the theology of those churches underwent major changes, especially under the influence of Hosea Ballou, who single-handedly moved Universalism from a Calvinistic to a Unitarian base. Like the Unitarians, the Universalist churches were also prominent in social action, especially cases involving freedom of religion. In short, the Unitarian and Universalist bodies were coming closer together, and it was inevitable that they should begin cooperating formally. From the turn of the 20th century there were joint enterprises, e.g. in youth activities and social action, and in 1961 the two finally merged into the Unitarian Universalist Association.

So the key element in the theology of UUism in North America appears to be change. But in another respect we have remained true to the thought of Servetus and Socinus. These men were known for their doctrine of the unity of God; but even more important than theology may be the way they arrived at this doctrine, since that illustrates the kind of thinkers they were. They, and Dávid and Priestley and Ballou and Channing and Parker and Reese, have all confirmed the dictum of Earl Morse Wilbur, who said that ours is:

“a movement fundamentally characterized...by its steadfast and increasing devotion to these three leading principles: first, complete mental freedom in religion rather than bondage to creeds or confessions; second, the unrestricted use of reason in religion, rather than reliance upon external authority or past tradition; third, generous tolerance of differing religious views and usages rather than insistence upon uniformity in doctrine, worship or polity. Freedom, reason and tolerance: it is these conditions above all others that this movement has from the beginning increasingly sought to promote.”

© Reprinted with permission of Starr King School for the Ministry.

Servetus, or Miguel Servet, was a Spanish Catholic who had become a geographer and editor in Paris, then a physician in southern France. In that year, he published a book, The Restitution of Christianity, in which he repeated assertions he had made in his earlier writings: That the doctrines of the Trinity and infant baptism made no sense.

The order for his arrest went out, and one Sunday morning soon thereafter he was spotted in a Genevan church, arrested, tried for spreading heresy and executed, with a copy of the Restitution strapped to his thigh (or, according to some sources, his arm).

The death of Servetus was approved by the church leaders of the time, but not by all its ministers or laymen. His writings provided a stimulus for, among others, two Italians living in Zurich: Lelio Sozzini, who was impressed not only by Servetus’ doctrine but also by his method of thinking — basing his thought on reason as much as Scripture — and Giorgio Biandrata.

Both men went to Poland in 1558, Sozzini for a few months and Biandrata to stay. There they joined the liberal wing of the Polish Reformation, the so-called Minor Church, and helped to make it part of the Reformation’s left wing. When Biandrata left Poland five years later the Minor Church was in a weak condition, but twenty years after that its leadership was taken over by Fausto Sozzini, or Faustus Socinus, who had first absorbed liberalism from the papers willed to him by his uncle Lelio.

Socinus made Poland a stronghold of liberal Christianity for almost a century; the church he built and the theology he articulated were known as Socinianism, until the movement was destroyed by a decree banishing all Socinians. Some of the exiles went to Transylvania; others to Holland, the country where they felt they would have the best chance of practicing their religion.

Meanwhile Biandrata had been called to Transylvania to be the personal physician of King John Sigismund. There he spoke of his religious views with some of the leading citizens of the country, one of whom embraced them with alacrity. This was Ferenc Dávid, a former Catholic who had embraced Lutheranism and then Calvinism, and who under the influence of Biandrata now became the leader of the anti-Trinitarian movement.

In 1568 Ferenc Dávid succeeded in persuading the king to issue the broadest toleration edict in Europe at the time, granting the Socinians the same level of toleration as was already enjoyed by the Catholics, the Lutherans, and the Calvinists. (It was in the same year — 1568, just 15 years after the death of Servetus — that Dávid coined a new name for his group: Unitarians, or believers in one God, not three.)

But Sigismund’s sympathy for the Unitarians did not extend to his successor, and in 1578 Dávid was thrown into a dungeon, where he died a year later. The Transylvanian church survived, though greatly weakened, through the centuries. Its direct descendent today is an ethnic, Hungarian-speaking denomination in Rumania.

Holland, we may remember, was the refuge of some of the Polish Socinians; there were also many contacts between one of its religious groups, the Remonstrants, and Transylvania. These Remonstrants were in the late 17th century printing English translations of Socinus and other liberals, and smuggling them across the Channel. A result was a growing interest in liberal religion among certain English churchmen, among them the Anglican Theophilus Lindsay and the chemist Joseph Priestley, who professionally was not a scientist but a Dissenting minister.

Priestley was the leader of the group that in his time came to be called Unitarians, until he was driven from England in 1794 by continuing threats to his life. So he came over to the new United States of America, where he settled in Northumberland, Pennsylvania, meeting regularly with a group of twenty to thirty people to discuss religious matters. This was not a formal church; but two years later he helped found in Philadelphia the first American society calling itself Unitarian. Even so, Priestley did not originate liberal Christian thought in this country.

Half a century before Priestly there were two ministers, Charles Chauncy and Jonathan Mayhew, who had preached heretical doctrines including the unity of God; and in 1785 their disciple, James Freeman, persuaded the members of his church, King’s Chapel in Boston, to adopt changes in the wording of its Prayer Book which made it de facto the first Unitarian church in America, though it never acknowledged the fact in its name.

The later history of the Unitarian movement in North America is one of change and development, a change much more striking than what has taken place in any other national Unitarian movement. For whereas the Unitarians in Rumania worship and believe today just about as they did four centuries ago, and those in England do not seem at times to have changed much more, in this country most observers would say that we have little in common with the Philadelphia Unitarians to whom Joseph Priestley spoke in 1796.

In the 19th century our own great Trinity — Channing, Emerson, and Parker — moved us from a totally Christian body to one open to the other religions and philosophies of the world, and in the early 20th century Curtis Reese and John Dietrich allowed us to embrace even a non-theistic religion.

The same is true of the other half of our UU movement. In England in the 1760s James Relly preached a doctrine of universalism, which held that since God was a loving God, it was inconceivable that he could condemn anyone to everlasting torment, and there were therefore no such place as Heaven or Hell; all people would eventually be saved. A disciple, John Murray, came to North America in 1770 and began preaching the doctrine, which merged with views already being propounded, especially in Philadelphia by Benjamin Rush and Dr. George de Benneville — yet another physician prominent in our history.

Murray went on to found Universalist churches in New England, but in the following century the theology of those churches underwent major changes, especially under the influence of Hosea Ballou, who single-handedly moved Universalism from a Calvinistic to a Unitarian base. Like the Unitarians, the Universalist churches were also prominent in social action, especially cases involving freedom of religion. In short, the Unitarian and Universalist bodies were coming closer together, and it was inevitable that they should begin cooperating formally. From the turn of the 20th century there were joint enterprises, e.g. in youth activities and social action, and in 1961 the two finally merged into the Unitarian Universalist Association.

So the key element in the theology of UUism in North America appears to be change. But in another respect we have remained true to the thought of Servetus and Socinus. These men were known for their doctrine of the unity of God; but even more important than theology may be the way they arrived at this doctrine, since that illustrates the kind of thinkers they were. They, and Dávid and Priestley and Ballou and Channing and Parker and Reese, have all confirmed the dictum of Earl Morse Wilbur, who said that ours is:

“a movement fundamentally characterized...by its steadfast and increasing devotion to these three leading principles: first, complete mental freedom in religion rather than bondage to creeds or confessions; second, the unrestricted use of reason in religion, rather than reliance upon external authority or past tradition; third, generous tolerance of differing religious views and usages rather than insistence upon uniformity in doctrine, worship or polity. Freedom, reason and tolerance: it is these conditions above all others that this movement has from the beginning increasingly sought to promote.”

© Reprinted with permission of Starr King School for the Ministry.

Mission Statement: LCUUC is a diverse religious community supporting one another in our spiritual search for truth, meaning and compassionate connection. Based on the Unitarian Universalist Principles and the transforming power of love, we strive for positive change in the world.

Find us at:

Lake Country Unitarian Universalist Church W299N5595 Grace Drive Hartland, WI 53029 (262) 369-1703 [email protected] [email protected] Calendar |

Hours:

Administrative Hours: Tues, Weds, Fri. 8am - 4pm (Contact for an appointment) Rev. Matt Aspin, LCUUC Minister Mon, Tues, Weds. 9am - 5pm (Contact for an appointment) Juliet Rogers, Coordinator of Family Ministry (Contact for an appointment) Tristan Strelitzer, Music/Choir Director (Contact for an appointment) |